Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC) and Lost Arts of Nepal crowdsource art and cultural objects from around the world.

by Kate Fitz Gibbon (published 3 February 2021)

[Please note: This article was updated on February 3, 2022 to distinguish the repatriation work of Roshan Mishra, who created the Global Nepali Museum Database from his work on the ‘team’ at the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC), and also from his professional work as director of the Taragaon Museum, which collects and displays documentation of Nepali heritage by scholars at its Nepal Architecture Archive. Neither the Saraf Foundation, an umbrella organization nor the Taragaon Museum are involved in the repatriation campaign. CPN thanks Roshan Mishra for clarifying that although individuals involved in the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign work for several different Nepalese heritage organizations, the NHRC and its activities are completely independent from them.]

Citizen activists in Nepal at the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC) and the online community Lost Arts of Nepal are asking foreign museums, collectors, and art galleries to return objects that they say left Nepal in violation of its export laws. One activist, Roshan Mishra, has built a database of Nepalese objects in foreign museums that can be compared to old photographs, drawings and scholarly documentation to identify their original location in Nepal. Others are crowdsourcing images from galleries and auction houses. The activists use social media to press for the return of objects, arguing that Nepalese law prevents export of objects over 100 years old. Although they cannot act officially, the activists have succeeded in having objects pulled from auction and, importantly, they have stimulated the long-neglectful Nepalese government to negotiate returns with foreign museums.

The picture of a nation seeking return of its gods – as the activists have characterized their campaign – is more complicated than it appears on the surface. Restoring gods to village temples and public monuments from which they were stolen is a righteous cause. But in the 30-70 years since sculptures of gods were taken, many have been replaced with new images that have their own worshipful spaces in village life. It is also questionable whether antique stone sculptures that were once left along roadsides would ever be safe again, even from accident. Returning sacred sculptures to Nepalese museums seems an inadequate solution; it would transform them into objects for visiting tourists to pay to see and for scholars to study in the Western mode, not for traditional worship. (Or at least for a different kind of reverence, since in much of the developed world, museums are a modern form of sacred space.)

There are also questions about the key role that objects from Nepal and neighboring Tibet have played as messengers around the globe for Buddhist and Hindu thought. As well as being distinct, historical objects of art and connoisseurship, Nepalese and Tibetan artworks are displayed in several museums in ‘shrine rooms’ intended as religious spaces and encouraging visitors to understand the spiritual qualities they embody. Many objects, such as the small bronze sculptures, paintings, books, and decorative works that came from shrines in private homes were sold by Nepalese who held rights of private ownership. Some of these objects now belong to archives, research and educational institutions, spiritual communities, or simply to people influenced by Buddhist or Hindu world views.

Objects from Tibet, many of which were made by Newari Nepalese craftsmen, have very different roles than as ‘national heritage.’ The outside world has an obligation to steward the relics of a Tibetan culture that was deliberately destroyed by Communist Chinese forces. (The 14th Dalai Lama spoke many times in the 1980s about the importance of collectors and museums safeguarding Himalayan art and artifacts so that Tibetan culture could be preserved for future generations.) Given the continuing repression and sinicization of Tibet and ongoing concerns about Chinese expansionism, there are preservationist counter-arguments against holding all examples of a culture in any single basket.

Background

The English language publication in 1998 of Jürgen Schick’s The Gods Are Leaving The Country; Art Theft from Nepal first made public the theft of idols from shrines and monuments in the Kathmandu Valley in the second half of the 20th century. Schick’s book made clear that the Nepalese government had not only failed to protect historical monuments of great importance, even within the capital of Kathmandu, but that officials had ignored or been complicit in the removal of sacred statues. The situation of temples, stupas, and shrines outside of Kathmandu was even more precarious. Traditionally, local shrines and temples had been supported by the communities surrounding them. The communities’ ability to maintain them had been decreasing for decades as a result of village and rural impoverishment under Nepal’s oppressive feudal structure.

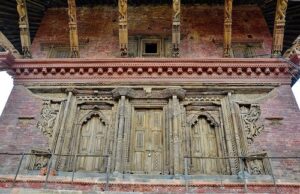

Longstanding concerns regarding the loss of Nepalese architectural heritage to negligence and decay prompted the creation of the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) in 1991. Originally a western (and collector) sponsored organization, the KVPT has saved or restored dozens of buildings from temples to palaces in the valley and helped to train a modern cadre of Nepalese architects who have continued its work to restore important monuments, many of which were damaged again in the devastating, 7.6 magnitude earthquake of April 2015. Unfortunately, experienced Nepal observers such as the journalist Thomas Bell report that officials have failed to protect, maintain, and restore historical monuments even when record amounts of foreign aid flowed to Nepal for that purpose after the 2015 earthquake struck Kathmandu.

Jürgen Schick’s book highlighted the looting of sculptures and decorative elements of temples and shrines. It compared photographs of objects in situ in Nepal’s temples and monuments to pictures taken in the 1980s of empty plinths and broken architectural mountings where wooden, bronze, and stone sculptures had once stood. Photographs of freestanding sculptures now held in place by iron fastenings or screens showed the attempts by local communities to prevent further thefts from Nepal’s mostly open air shrines.

It is noteworthy that Schick also blamed the rapid transformation of traditional culture and neglect of cultural heritage on the flow of millions of dollars in development funds in the late 20th century into an impoverished country of largely illiterate mountain farmers. He argued that modern life, with its array of desirable but expensive commodities (motorcycles, radios, telephones, and other goods) had undermined traditional worship, community cohesion, and the ‘magic’ of Nepal. Schick believed that much more than gods had been lost; he hoped for an awakening, a public movement that would turn back time and recover a pristine Nepal without the corruption, noise and pollution the 20th century had brought. Yet despite Schick’s eloquence and his work to make the losses clear, he acknowledged that the Nepalese government was never moved to make an issue of temple thefts or to hold those responsible accountable. As Schick states in The Gods Are Leaving the Country (p39):

“There is, to be sure, a law stating that no work of art more than one hundred years old may be taken out of the country. That’s what is written on paper; the reality of the situation makes a mockery of the law.

Nepalese have been waiting in vain for effective countermeasures by the state, even though it is normally the duty of the government to protect the nation’s art treasures. Thus it is up to the affected persons themselves, the faithful, the priests, the temple watchmen, to provide assistance on their own, to the extent they can.”

The repatriation players

Two decades later, the Nepalese state has still failed to act – either to recover objects, preserve more than a few monuments, or protect those still at risk. Over the past two years, however, the citizen activists in Nepal, inspired by non-governmental repatriation activists in India, have demanded the return of Nepalese objects from museums and collections around the world.

Roshan Mishra, whose professional work includes directorship of the Taragaon Cultural Center and Museum, has taken an important role through his personal work to build the Global Nepali Museum Database, a resource for identifying lost works. Mishra[iv] has personally compiled a database of some 3000 objects from Nepal in the holdings of museums around the world. He is also one of the team of campaigners and volunteers at NHRC, which includes among its members Nepali publisher and writer Kanak Mani Dixit and conservation architect Rohit Ranjitkar.

While in the past, heritage professionals have focused on retrieving religious sculptures and artifacts from monuments, the citizen activists have spread a far wider net, seeking books, furniture, textiles and more.

The activists at Lost Arts of Nepal and Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC) are among the most highly educated members of Nepalese society. Despite the excellent intentions of the activists, it is not clear that the goals of this largely elite group align with the rural Nepalese who continue to worship the modern sculptures that have replaced those taken from shrines.

The campaign to bring back art to Nepal has often been characterized as “restoring stolen idols” or “bringing back the gods to the country.” However, there is a debate even among those Nepalese active in the art community regarding whether sculptures recovered from Western museums and collections should be returned to shrines where they were worshiped as gods, bedecked with colored paint and hidden behind tinseled fabrics – or be held in museums where they will function as they do in Western museums, as objects marking historical stages in religion, politics, art history and other abstract art historical narratives. Some Facebook comments on their sites point to the attention and study that Nepalese collections in Western museums have inspired; seeing the Western model of curation and scholarship as valuable today. However, for many, including leading activist at the NHRC, Kanik Mani Dixit, it is inappropriate simply to take a god from one museum and place it in another, where it is deprived of its community and environment.

Government is reacting to activist demands

In the past, the Nepalese government was extremely reluctant to publicize thefts from temples or illicit export of objects from private shrines – involvement by high level officials in sales and providing export documents has been an ‘open secret’ in Kathmandu for decades. Now, using social pressure both inside and outside Nepal rather than legal means, the activists have induced its government to take a more active part and to facilitate returns of objects they have identified.

Although these groups work through the Nepalese government to contact foreign holders of Nepalese art, the citizen-activists are clearly the driving force behind returns.

The activists’ claims to specific objects are based on diligent research into long-ago disappearances. A legally valid claim has to start with some evidence that an object was once in Nepal. To do so, they compare antique drawings and old photographs of objects in situ in Nepal to pieces in foreign museum collections and circulating in the art market. A great many vintage images exist. These were made by Western, Indian, and Nepalese scholars, visiting anthropologists, and students of eastern religion who documented Nepal’s thousands of antique temples and shrines in the decades since the 1950s. Linking these early records to global museum collections is possible because of many major museums’ commitment to making their entire collections public and accessible via the Internet.

When there is a direct correlation between an object in a foreign collection and its documentation in Nepal, the activist groups forward the information to Nepal’s Department of Archaeology in the Ministry of Culture, which works through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to contact representatives of the country where the objects are now located.

Discussions between Nepalese officials and foreign museums have followed, sometimes involving law enforcement in the countries where objects are located. The cultural ministry of Nepal has been pleased to accept the return of objects that left the country in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. It is worth noting that the objects identified by these activist groups have not been found in obscure museum collections; most have been on display in major global museums for several decades or more, published in auction catalogs or exhibited on well-known gallery websites.

The objects so far identified have not been recently exported from Nepal – most were owned by collectors who acquired them in the 1950s-1980s who later donated them to public collections. The work of the citizen activist groups has resulted in several returns already. A 12th century statue of Laxmi-Naryan said to have been taken from Nepal thirty-seven years before was returned by the Dallas Art Museum to the government of Nepal in April 2021.[i] The Art Gallery of New South Wales in Australia is in discussions with Nepal regarding a strut with carved figures from the Sulima Ratnesvara temple. The Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign has also taken credit for the removal from auction of a group of carved and gilded figures that once adorned a temple strut in Patan.

The Facebook page of the Lost Arts of Nepal group features crowdsourced images of dozens more objects in museums from Lahore, Pakistan to Singapore and Taipei. The researchers have paired old photographs with objects from the websites of galleries and auction houses in the UK, US, France, and Hong Kong. What is usually not available, however, is evidence of how the objects left Nepal, whether smuggled clandestinely out of the country or exported with permits obtained from government officials. The citizen activists do not publicly address the culpability of officials in past losses, a subject that could make the Nepalese government uncomfortable.

These one-to-one comparisons also cannot show how many good-faith buyers’ hands they passed through. Few present day collectors purchased objects directly in Nepal. Museums received objects primarily through donation. The dates by which the researchers identify the objects’ removal from Nepal are more twenty-five years – and in many cases fifty or sixty years before.

The 20th century art trade in Kathmandu

Interviews with foreigners who were living in Kathmandu between the 1960s and 1980s paint a different picture from the laws on paper of how the art business worked.

According to statements by former residents, most stone sculptures were collected by dealers (mostly Nepalese and Tibetans) from villages off the beaten track. The dealers connived with powerful landowners and officials who could command the removal of objects from communities and substitute the older sculptures with newly carved images. According to the former residents, carved decorations and architectural materials were taken from both active, existing shrines and disused temples. These objects were sold in Kathmandu, not in shopfronts but from backrooms. There were also hundreds of smaller bronzes from private home shrines that were sold by members of the wealthy elite.

Sources who lived in Nepal during the heyday of the export trade and press reports today agree that the export of temple idols, architectural elements, Hindu and Buddhist books, paintings, and ceremonial artifacts was facilitated by Nepalese officials, including members of the Rana oligarchy[ii], the royal family, and politicians still wielding power today.

In order for the trade to flourish, government officials had to be involved at every level. The most important Nepalese and Tibetan dealers were able to sell objects brought in from Tibet or taken from temples and shrines in Nepal because they were allied to elite families or had relatives who held important government posts. Permits were required for export. However, it was an accepted part of the job of professional shipping agents to obtain permits from the government for items to be exported as well as to safely pack them and arrange for air transport. Although many Nepalese and Tibetan objects were taken overland by traders and Tibetan refugees and then sold in India, airfreight was the safest method of reaching Western markets from landlocked Nepal.

In a recent article, Gautam Vajra Vajracharya cites to cases of destruction of temple idols beginning in the 14th century and to what he calls “the first theft” of an idol of Naryan in 1765; he declines to name a culprit but says the theft of idols began only on the arrival of the British in India. According to Vajracharya, the promotion of Nepalese art through international exhibitions in the 20th century led to a rapid expansion in international collecting:

“During the reign of King Mahendra and a few decades before that, Nepali artefacts… had started to be respectfully displayed in various international museums. From an immediate point of view, this was a matter of pride for Nepal… King Mahendra’s intention was to make Nepal famous not only as an independent country but also as a beautiful country in the lap of the Himalayas full of its own art. So King Mahendra was overjoyed when Stella Kramrish, a senior curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, proposed organizing the first international exhibition of Nepali art [in 1964]. It was not difficult to get permission to take Nepali artefacts out of the country for some time for the exhibition to be held outside the country.”

Vajracharya also notes that King Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev (ruled 1955 to 1972) gave an important 12th century statue of Vishnu to Chester A. Ronning, Canadian Ambassador to India, that is now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Nepal is home to powerful competing forces within its strong caste system: the descendants of Buddhist merchants and priests, urban Sresthas, village patrons, Brahmin kingly councilors, and various low castes.[iii] Vajracharya also hints that these parties’ role in land reform and the impoverishment of Newar communities was a factor limiting public religious activities and that the unfunding of temples enabled idols to “disappear unnoticed.” The 1966-2006 civil war with Maoist insurgents in the countryside did nothing to remedy the hardship and privations of country people.

In the 1960s-1980s heyday of acquisition of Nepalese art, privately owned artifacts from a variety of sources, legitimate and illegitimate, flowed out of Nepal to collectors and dealers from Western countries and Japan. The largest dealers of ancient and antique Nepalese artifacts were Tibetans, known as tough men, and one major and respected Newari dealer. By the 1990s, the more public outflow was greatly reduced, partly because easily available objects had been depleted, partly because buyers sought out more popular Tibetan artifacts inside Tibet, and partly because increasing knowledge about the monetary value of antique goods had concentrated the remaining Nepalese market in the hands of elites with government connections who were immune from legal repercussion.

A marketplace for Nepali and Tibetan objects

By no means all ancient and antique goods sold in Nepal in the 1960s-80s were of Nepalese origin. Many antiquities marketed in Nepal from the 1950s through the 1980s were artifacts brought out of Tibet as a result of the wholesale destruction of temples and monasteries and Tibet’s occupation by China. Religious leaders, humble monks from lamaseries and other religious organizations and refugees carrying personal possessions fled to Nepal and to northern India, bringing whatever precious religious texts and ceremonial objects they could carry with them. Western interest in the art of the region was greatly spurred by the arrival of thousands of examples of Himalayan art. India was the first marketing destination for Tibetan art in the late 1950s. Many ‘Tibetan’ artifacts had in fact been made centuries before in Nepal by Newari artists and artisans. The destruction of Tibetan heritage by China’s government and support for western collecting by the Dalai Lama also made foreign collecting of Tibetan art an issue of preservation first.

During the 1950s and 1960s, when over 90% of the lamaseries and other religious and ruling institutions in Tibet were destroyed by Chinese troops, Chinese law protected ‘revolutionary culture’ and all historical materials associated with ‘the advance of communism.’ Ancient and antique temples, grottoes, and pre-revolutionary historical monuments were ‘protected’ but not open to the general public until such time that these relics could be shown to illustrate the fallacies of imperialism and capitalism.

After Tibet opened to Western travelers in the later 1980s, the market for Tibetan goods expanded and the Nepalese market declined. Tibetan artifacts were considered more important and less ‘provincial’ than Nepalese works. By the mid-1990s, for the most part, Nepalese bronzes and stone sculptures were no longer accessible to Western buyers, but ethnographic objects of wood, masks and hill tribe materials were sold widely in Kathmandu. Antique ethnographic objects still needed museum stamps for export and received them.

Addendum: Notes on Nepalese law

Nepalese laws on cultural heritage evolved in similar forms with other aspirational heritage legislation in the 1960s and 1970s in undeveloped countries around the world. Laws were written without the administrative or enforcement support to implement them. Historically, the focus of Nepal law has been on monuments and objects of reverence of Nepali or other Buddhist origin. Private ownership of both antiquities and monuments was permitted although the government could purchase objects or sites at risk for a ‘reasonable price’. The types of objects described as “archaeological objects” under Nepal law through 1968, and under the 1969 and 1970 laws could be ambiguous or obscure.

Even Nepal’s 1994 heritage legislation did not place conservation and preservation exclusively in government hands. The 1994 law distinguished between private and State ownership:

“(5ka) Except the buildings under the private ownership all other ancient Monuments and sites related with monuments of the protected Monument Zone will remain under the ownership of with [sic] DOA [Department of Archaeology].”

“(5kha) On the basis of ownership all ancient monuments and sites related to monuments shall be divided into two categories as Public and Private monuments.”

The 1994 law attempted to require regular maintenance and conservation of temples and shrines. However, the Department of Archaeology was only tasked with conserving major monuments:

“(1) The Conservation, maintenance and renovation of the ancient monuments under private ownership which are inside the Protected Monuments area shall be carried out by the concerned person. Provided that if it is deemed necessary to conserve, maintain and renovate the private ancient monuments which are of importance from the national and international view point, by the Department of Archaeology, the Department of Archaeology may, conserve, maintain and renovate such ancient monuments.”

At the same time, the government pushed responsibility for maintenance on to religious organizations:

“3E. Operation of Religious Temples, Monasteries, etc. (1) The person operating a religious temple, monastery etc. shall use up to fifty percent of the amount of the donation offered to such temple or monastery for the conservation of the temple or monastery and for bringing reformation in its surrounding environment.”

One can assume, based upon Nepalese law in 1994, that during prior decades when most Nepalese artifacts were taken from the country, export without a permit was unlawful, but Nepal did not claim government or national ownership of antiquities. Religious sculptures, certain shrines and other religious edifices, ancient monuments on private lands, and family gods and religious paraphernalia such as thankas, manuscripts, and paintings were lawfully held in Nepal under private ownership. At the same time, export prohibitions were enforced ‘more or less’ against tourists and other casual buyers but this did not prevent export by well-connected individuals in the hierarchy.

The 1970 law, which was in force during the latter part of the period when most objects left Nepal, states that the identification of what constitutes an archeological object prohibited export is in His Majesty the King’s discretion. Given the open commercial trade and frequent export of various ethnographic materials, books, metalwork, costumes, woodcarvings, antique rugs and textiles from Nepal in the 1970s and 1980s without restriction, in practice, Nepalese export laws do not appear to have pertained to objects other than religious materials at this time or to have been strictly enforced.

Under Nepalese law, objects requiring a permit for export included antiquities that were imported into Nepal without official registration. Nepalese laws also allowed registration of foreign cultural property and its re-export, but registration was practically unknown. There was unlikely to have been any registration of Tibetan objects brought into Nepal by refugees.

———————————————————————————————————————-

[i] The sculpture of Lakshmi is said to have been catalogued in a Sotheby’s auction in 1990.

[ii] The Rana dynasty were the effective rulers of Nepal from 1846 to 1951 as hereditary prime ministers, but they maintained a figurehead king of the Shah dynasty. See Rana dynasty, and Shah dynasty.

[iii] Contested Hierarchies: a Collaborative Ethnography Of Caste in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Edited by David Gellner and Declan Quigley. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

[iv] Roshan Mishra is the son of well-known Nepalese artist and writer, the late Manuj Babu Mishra. Roshan Mishra also plans to build a museum dedicated to the work of his father, the Mishra Museum.